Dye in the Rip

A rip blog from Professor Rob Brander….

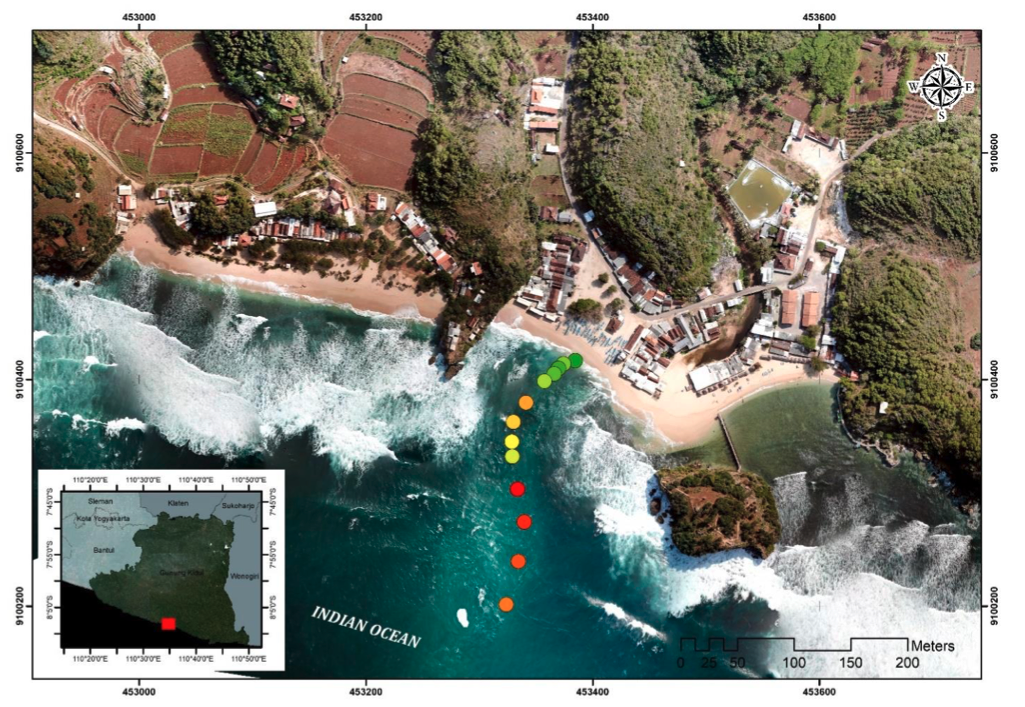

Figure from a new study using dye to measure rip speed : Identification of Rip Current Hazards Using Fluorescent Dye And Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (A Case Study Of Drini Beach, Gunungkidul, Indonesia)

Various types of coloured dye have been used in rip currents for many years as an educational tool to help people better understand the speed and trajectory of this common beach hazard. It’s proven to be an increasingly popular method and it’s not hard to see why: it’s a dramatic visual effect that brings an often ‘unseen’ and mis-understood hazard to life, both in person, and through the use of still images and video.

From a personal perspective, I’ve given many presentations to university, high school and primary students as well as the general public and it’s the visual imagery of rip current dye releases that they remember (and like) the most – it’s always a high point of my undergraduate university field trips!

However, to date, few scientific studies have used dye to provide actual quantitative Lagrangian measurements of rip current flow. ‘Lagrangian’ refers to methods used to track currents that ‘go with the flow’, such as drogues, drifters and sometimes rip floaters (people!).

It’s therefore encouraging to see a new study by Indonesian researchers from the Universitas Gadjah Mada in Yogyakarta open for discussion in the journal Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences. They released an environmentally friendly fluorescent dye (Uranine; Fluorescein is another popular type used) into a rip current at Drini Beach, a nearby tourist beach and used aerial drone footage to measure the flow speed.

Scientifically it’s always interesting to see new rip current measurements from different environments and what is particularly unique about this rip current is that it occupies a deep channel between coral reef flats. Technically it’s a type of boundary rip current called a reef rip current, a type that hasn’t received much attention in the literature. These rips are structurally persistent in location and represent a significant hazard to swimmers.

It’s good to see that the dye imagery from the study received significant online news and social media attention in Indonesia. I’ve visited that coastline at nearby Parangtritis beach and it’s a nasty and dangerous surf zone with lots of rips that is not safe for swimming. This type of study is therefore invaluable for its educational benefits to both tourism operators and tourists in the region. We need more studies like this globally!

For more safety information about rip currents please visit: